He is a transdisciplinary scholar interested in restorative cultural practices…

The Cultural Ecology of Conflicts in Africa

Africa for a long time has been profiled as having the highest statistics of violent conflicts in the world. For a long time too, the treatment of conflicts in Africa involving communities and national armies has revolved around conventional mechanisms that have excluded useful traditional approaches of peace creation which are of much significance especially in the current politically foggy environment we live in. In this piece, I want to undermine African Union’s prominent proclamation of ‘Silencing the Guns’ by 2020 and instead suggest that we redress concerns of ‘unjustness’ that drive communities to arm themselves against each other or against what many still consider a ‘predatory’ state.

Seven years ago, member states of the African Union gathered in Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the organization’s founding. It is also at that gathering in 2013 that representatives from across the continent singled out armed conflict as the biggest barrier to development on the continent. African leaders reaffirmed their commitment to address the structural root causes of violent conflicts in Africa, pointing out that ‘Silencing the Guns’ was a Flagship Project of Africa’s Agenda 2063 that required all Africans to work together towards ending all wars, civil conflicts, gender-based violence, violent conflicts with the hope of preventing genocide.

Sadly, as we draw the curtains for 2020, the guns are yet to fully fall silent. Indeed, latest statistics bear out the impression that conflict on the continent is actually getting worse, not better. The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, which monitors incidents of conflict around the world, found that there had been 21, 600 incidents of armed conflict in Africa in 2019. For the same period in 2018, that number was just 15, 874. That represents a 36% increase.

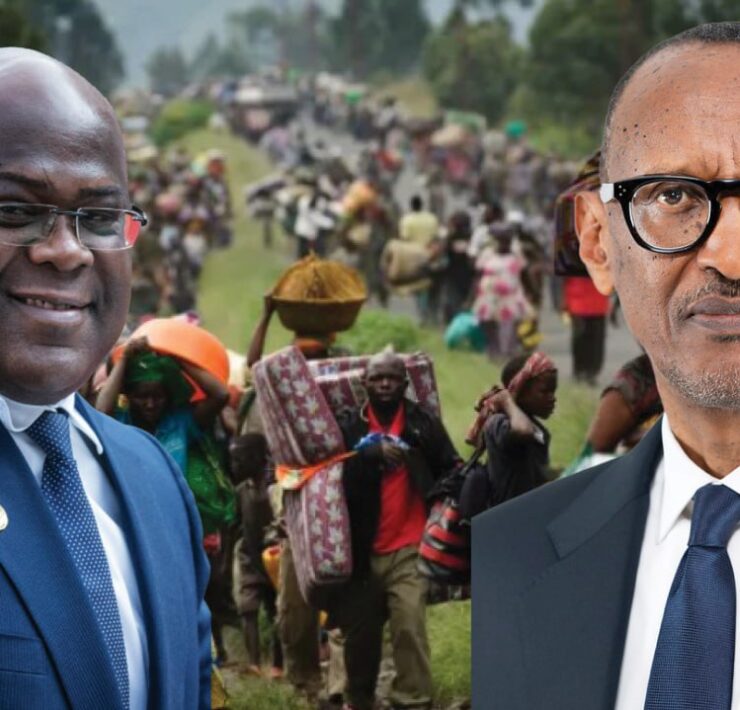

In the recent past, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Somalia, South Sudan, Nigeria, the Central African Republic (CAR) and Libya, have seen tens of thousands of people killed and millions more displaced. The war in the DRC alone is one of Africa’s deadliest having claimed the lives of more than five million people since 1998 when it began. In the first half of 2019, about 732,000 new displacements were recorded, 718,000 associated with conflict and 14,000 associated with disasters, posing additional challenges for the new DRC government. In South Sudan, since civil war broke out in 2013, about 380,000 people are reported to have been killed and more than two million have been forced to flee their homes. A 2015 peace deal fell apart after clashes between government forces and rebels.

In Central African Republic (CAR), the conflict situation has persisted for more than seven years, insecurity and attacks against civilians, humanitarians, and UN peacekeeping forces has led to thousands of deaths and has internally displaced more than 600,000 people. In Nigeria, more than 30,000 people have been killed by Boko Haram insurgency that began in 2009 with the aim of confronting what it perceived as the westernization of Nigerian culture. About two million people have fled their homes and another 22,000 are missing, believed to have been conscripted to the group. The group’s influence is said to have extended to neighbouring countries, including Cameroon, Chad and Niger.

In Somalia which has had a civil war since 1991, the Al-Shabaab militant group emerged as an offshoot of the Islamic Courts Union which controlled Mogadishu in 2006, while a transitional federal government was in exile in Kenya. Despite gains against the group, Al-Shabaab insurgents continue to launch sporadic attacks against civilians and the government. In Libya, conflict has persisted by armed groups since the ouster of Colonel Gadafi in 2011. In spite of a UN arms embargo, parties to the conflict continue to draw on international support for weapons.

The ongoing Covid-19 pandemic aside, conflicts continue to pose a serious challenge to Africa’s growth and development agenda. Violent conflicts in Africa continue to exert a heavy toll on the continent’s communities, polities and economies, robbing them of their developmental potential and democratic possibilities. As Malawian historian Paul Zeleza meticulously argues, the causes of the conflicts are as complex as the challenges of resolving them are difficult. But their costs cannot be in doubt, nor the need, indeed the urgency, to resolve them if the continent is to navigate the twenty-first century more successfully than it did the twentieth, a century that was marked by the depredations of colonialism and its debilitating legacies and destructive postcolonial disruptions.

The magnitude and impact of these conflicts are often lost between hysteria and apathy – the panic expressed among Africa’s friends and the indifference exhibited by its foes – for a continent mired in, and supposedly dying from, an endless spiral of self-destruction. More importantly, Zeleza points out that the distortions that mar discussions and depictions of African conflicts are rooted in the long-standing tendency to treat African social phenomena as peculiar and pathological, beyond the pale of humanity, let alone rational explanation. Yet, from a historical and global perspective, Africa has been no more prone to violent conflicts than other regions. Zeleza, who is at present the Vice Chancellor of United States International University – Africa (USIU-A) in Nairobi, further explains that Africa’s share of the more than 180 million people who died from conflicts and atrocities during the twentieth century is relatively modest: in the sheer scale of casualties, there is no equivalent in African history to Europe’s First and Second World Wars, or even the civil wars and atrocities in revolutionary Russia and China. The worst bloodletting in twentieth-century Africa occurred during the colonial period in King Leopold’s Congo Free State.

This is not to diminish the role that African Union has played in curling violent conflicts on Africa. It is merely to emphasize the need for more balanced debate and commentary, to put African conflicts in both global and historical perspectives. For a start, not only are African conflicts inseparable from the conflicts of the twentieth century – the most violent century in world history; many postcolonial conflicts are rooted in colonial conflicts. There is hardly any zone of conflict in contemporary Africa that cannot trace its sordid violence to colonial history.

Nearly 60 years after independence from colonial rule, sub-national territorial demarcations, political identities and the locus of authority remain deeply contested in most African countries. These issues continue to generate conflicts around constitutive features of state and nationhood and remain at the heart of political struggles in many societies including countries with consolidated international borders. In addition, regional and global economic, technological and ideological processes are reshaping notions of the relevant and legitimate boundaries of territories and identities. In most of Africa, regions and populations have been incorporated into the national polity in highly uneven ways, leading to real and perceived group exclusion. In such politically divided societies, violent conflict remains a serious threat because the distribution of political power are high-stake issues.

Conflict prevention, needless to say, is one of the most urgent tasks facing the African continent, as recent events in Angola, Sierra Leone, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) have demonstrated. To its credit, the African Union has initiated various treaties related to promoting peace, security and good governance. These instruments include; the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, the Convention for the Elimination of Mercenarism in Africa, Convention on the Prevention and Combating of Terrorism, The Non-Aggression and Common Defense Pact, African Charter on Maritime Security and Safety and Development in Africa, African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance as well as the Convention on Preventing and Combatting Corruption.

Despite these efforts by the African Union and various other stakeholders to establish peace in Africa, armed conflicts continue to persist in various parts of the continent. The nature of violent conflicts in Africa has changed since before independence when they were mostly ideologically-driven guerilla warfare. Many of the current conflicts are driven by prospects of political power or financial gain, with armed groups fighting to acquire valuable mineral resources, assert their ideology or address grievances.

Structural Violence

My argument from the start has been that in order to silence the artilleries, Africa needs an all-inclusive developmental agenda that will ensure poverty is eradicated, income distribution is improved upon and that social progress is sustained for all Africans. With these things in place, the guns will simply go silent. As many have argued, there are many factors that have played a role in limiting inclusive development in Africa. In his 2011 paper Running While Others Walk: Knowledge and the Challenge of Africa’s Development, another Malawian economist ThandikaMkandawire argues that development, especially in the African context, must be seen as a ‘liberatory human aspiration’ to attain freedom from political, economic, ideological, epistemological, and social domination. Arguably, even when it comes to economic development Mkandawire has also conceived development as a ‘liberatory human aspiration’. Issa Shivji, the Tanzanian legal scholar and other notable academics have also made supportive points.

That said, for a very long time, communities across Africa have been engaged in an emotional search for justice, whereas all we have received for an equally long time has been mere cheats, imperfect pictures borrowed from the Western world that present to us a simulacrum designed to win our assent to conceptions which are profoundly unjust.

Kenya’s ‘BBI’ Initiative

As a way of example, in Kenya, for instance, the ongoing Building Bridges Initiative (BBI) a political agreement between President Uhuru Kenyatta and leader of Opposition Raila Odinga aimed at redressing nine major issues identified as contentious that have often led to conflict since the country got its independence from Britain in 1963. The viability of such an elite-led initiative remains to be seen especially if it fails to address what Norwegiansociologist John Galtungtermed as ‘structural violence’.

In his seminal article ‘Violence, Peace, and Peace Research,’ Galtung described structural violence as an injury that is ‘built into the structure’ and manifests itself as inequality of power, resources, and life opportunities. Galtung argues that the failure to prevent injury, pain and suffering is as relevant to social and political analysis as is their perpetration. According to this notion of structural violence, everything that hinders individuals from developing their capabilities, dispositions, or possibilities counts as violence. This includes not only specific forms of targeted discrimination but also more diffuse forms of inequality.

Relevant in the present discourse of ‘silencing the guns’, the virtue in structural violence is that it opens up the category of violence so as to include poverty, hunger, subordination, and social exclusion. It makes it possible to conceive differential access to power and resources as a form of violence, shifting the category of violence away from surface phenomena toward a broad set of social relations.

Nigeria’s ‘SARS’ protests

Another example is the unravelling situation in Muhammadu Buhari’s Nigeria, where young Nigerians have taken to the streets protesting for reforms to the way the country is run and calling for the disbandment of the revered SARS(special anti-robbery squads) police unit, which had been accused of illegal detentions, assaults and shootings. Facing mounting pressure across the world, Muhammadu Buhari finally bowed and disbanded SARS on 11th October 2020. In spite of the disbandment, the demonstrations have persisted and have come to represent more than simply opposition to police violence, but a deep frustration with the status quo and the political class defending it. The protests in Nigeria and across the world reflect the disillusionment of young Africans across the world who see the post-Cold War political-economic settlement as delivering nothing but inequality, joblessness, climate catastrophe and downright misery.

On a positive note, it is not that long since Africa was engulfed in the so-called “fledgling democracies’ era – the 1990s, when most of Africa ushered in multi-party politics, replacing post-independence military rule or one-party political systems. Thanks to a wave of pro-democracy pressure by Africans themselves, coupled with the end of the Cold War, plural democracy as Africans know and see it in many parts of the continent today, was established.

Africa’s doomsayers did not give much hope to the new political dispensation, but more than 30 years on, democracy in Africa is still cresting the wave. Gone are the days when in some African countries’voters were offered the choice of picking a presidential or a parliamentary candidate on a ballot paper that carried just ruling-party candidates, or even worse, one candidate pitted against a symbol. Gone are the days of inexplicable political terms and ideologies such as “Nyayo Democracy”.

Fast-forward to 2020, and African democracy is slowly emerging out of the woodworks. The key question for all of us is What can African leaders, led by the African Union, do to enhance this trend – More so because the answer to their loud proclamation of silencing the guns may lie therein.

Subscribe now for updates from Msingi Afrika Magazine!

Receive notifications about new issues, products and offers.

What's Your Reaction?

PIN IT

PIN ITHe is a transdisciplinary scholar interested in restorative cultural practices as well as the role indigenous knowledge systems play in the administration of justice in Africa. Educated at Stanmore, he read Politics at Middlesex for his undergraduate degree and Human Rights for his postgraduate at Bickbeck College. He holds two further postgraduate degrees in Ethics and in Public Administration from Nairobi. Wanda is very interested in how knowledge is generated and applied in relation to community development. His current research interests cover: Restorative democracy in Eastern Africa; Afrikology; Community Sites of Knowledge and Indigenous knowledge systems; Epistemology, Ethics and Culture. gahokenya@gmail.com