Arab-Islamic Commemorative Plaques: An Evolution of Afrikan Religious Arts

Mr. Wanyama Ogutu is a scholar in the Master of…

Read Next

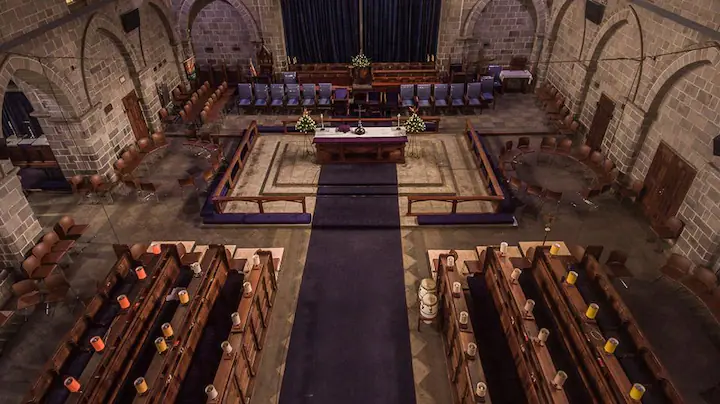

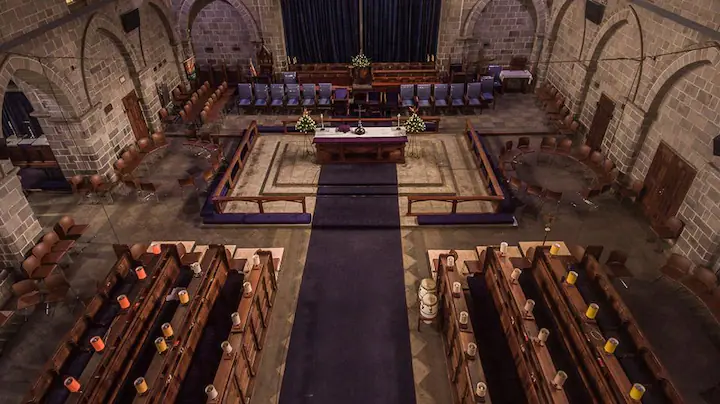

My two best friends, ‘one currently wearing a purple cassock hue with a sparkled pectoral cross neckless, and the other one is still wearing a blue cassock hue’, approached the main door. We spotted two stones plastered on the front of the door with engraved plaques. The first reads, “THIS STONE WAS LAID BY HIS EXCELLENCE THE GOVERNOR, SIR HENRY CONWAY, BELFIELD”. It dates to 1917. The other plaque commemorated the inauguration of the first bishop of the dioceses in 2002. My friend in the purple cassock whispered in my ear “It is a split of Nairobi dioceses to form the All Saints Cathedral Diocese”. We were fascinated to walk around the cathedral, where we stumbled on other incredible stones laid by the governors Sir Philip Mitchell in 1946 and Sir Robert Throne Coryndom in 1922. At that moment, the argument turned into an exhibition adventure. “This text on the stone plaque celebrates the indelible contribution of the cathedral missionaries’ founders,” one of the blue cassock’s friends interjected into our conversation.

We noticed two large metal plates in a semi-circle shape with the Kings of England emblem. It was inscribed with the names of fallen King’s Rifle soldiers in East Africa between 1914 and 1918, both Africans and Europeans involved in the First and Second World Wars. We saw other small and medium-sized metal plates on the same wall. We walked along the north aisle, north tower, lady chapel, archbishop cathedra, rose window wall, south chancel, alter, and back to the south aisle, where we came across a pin-up of different metal plates of different shapes. Some plates featured African wildlife symbols, the Queen of England emblem, East African rifle logos, the Early Missionary emblem, and the Christian crucifix symbol of the crucified Jesus Christ, among other iconography. As we walk around, we notice a few plates with geometric and gothic shapes around the edges. Some plates took on the architectural shape of the mosque. Other plates were simply mounted on wood and were not explicitly decorated. Some were inscribed with a few words in plain font without any borderlines or decoration. The most recent plates, dated 2009–2019, were sandwiched between the other plaques on the wall. We noticed that the metal plaque was made of bronze and iron, and some of it was glazed with silver and a golden hue. The majority of the plates were inscribed with a plain, simple font, and only a few had the beautiful calligraphy fonts of Carolingian and Old Roman. We recognized that most of the plaque was inscribed in high relief in a simple font. Others were inscribed in low relief and filled with white charcoal. I quickly noticed that those with high relief had attracted rust and dust, making them easy to read. When we finished our tour at the last plate in the south aisle, my purple cassock friend stared at us and said, “This plaque is a memorial to the next generation to understand the history of this church”.

I was perplexed by an Islamic-Arabic plaque on the cathedral’s south and north aisle walls. It had regular lines scribed on the rectangular portrait metal plate, probably measuring 100 cm by 50 cm in size. The two plates were characterized by the dome architectural shape seen in mosque buildings. It had iconography that was either the Islamic symbol of the crescent moon or Christian iconography. The surface of it was glazed with a golden hue. The plate’s edge was decorated with flora and instinctive elements of lines and geometrical shapes. Then commemoration messages were written in beautiful Islamic-Arabic calligraphy fonts. “Why would such Islamic-Arabic plates appear in the House of God?”, “What is the relationship between Islam and Christianity on this artifact?”. An African priest at the GAFFCON conference held in October 2013 in Nairobi, Kenya, speculated that All Saints Cathedral in Nairobi has the genealogy of the early Afrikan church in North Africa. He linked the history of the church to early Afrikan Christianity artifacts among the Kush people in Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia. He pointed to evidence from dome shapes, stone buildings, calligraphy manuscripts, and paintings of early Ethiopian and Egyptian churches. I promptly reminded him of other noteworthy reads to ancient churches such as Hagia Sophia and Pammakaristos. Today, those ancient churches are mosques and historical museums. This was due to the successful war between Islamic and Christian religions along the Red Sea, Near East, Spain, and North Africa.

For centuries, among the highly esteemed Islamic-Arabic items were a ceramic vessel, a dome of architectural design, and the art of calligraphy. The items or artwork are patterned with intrinsic flora and beautiful lines to honor God’s beautiful creation. Byzantine churches and even early mosques have dome shapes that sparkle with golden color harmonies and display regular floral and instinctive lines of calligraphy. The same depiction is observed on some golden, shiny plates on the north and south aisles at All Saints Cathedral, Nairobi. Instead of the Islamic-Arabic symbol on top of the dome shape, as seen in mosques, there is a variety of Christian iconography in letters and beneath a small red cross. The red crucifix is associated with the Christian faith doctrine, which believes Jesus Christ died on the cross for our sins. The iconography also reminds Christians of the holy war’s success in reclaiming artifacts besieged and captured in the cathedral by Muslim warriors. Many artifacts, including dome-shaped architectural designs and works of calligraphy, have been reinstated in modern churches. When you look at the tip of the dome shape at All Saints Cathedral, you see iconography in a red hue against a golden surface. The iconography on top depicts Christ as the head of the church, and the red color represents Christ’s blood as a substitute for our sin. The black inscription on the gold plate depicts successful evangelist missionaries among African territories. The beautiful messages are inscribed in a Carolingian or Roman font, which evolved from Sematic, Arabic, and Carolingian in the Roman Empire. The font style was an evolution of calligraphy, characterized by curves, arches, and line alignments. In the Islamic-Arabic religion, the art of calligraphy is depicted in the Koran; many believe it is God’s handwriting in heaven. The message is converted from Carolingian or Roman to English. English is the most commonly used language by the African congregation at All Saints Cathedral in Nairobi. It is imperative to acknowledge that the plaques were generated in an era of advanced technology.

Our ostensible conversation turned to an exhibition adventure at All Saints Cathedral, Nairobi. My purple and blue friend Cassock was astonished by the inedible insights into the commemoration plaque on the wall of the cathedral. We were surprised that All Saints Cathedral, Nairobi, houses a historical and memorable plate that dates from 1914–1936. Some plates are made of bronze and iron, and some are glazed with a golden color. Among the incredible commemoration plaques were two World War II plates with the names of soldiers, early Christian evangelist missionaries, the laid stones of the cathedral founder, and unforgotten clergymen. There are Arab-Islamic plaques on the aisle walls of the cathedral. The plaques are an aide-mémoire that Islam is a religion that assimilated Christianity’s culture and arts. Today, the exhibits of Arab-Islamic plaques, among others, at All Saints Cathedral, Nairobi, are reminders of the evolution of the Afrikan post-modern religion.

REFERENCES

- Bantu. V. (2016). Early african Christianity :Multiethnic Roots of Christianity Part II. retrieved on October 2019.https://jude3project.org/blog/2016/earlychristianitynubia

- Laurie S. A.(1994). A History of Western Art. (5th). New York, MH: McGraw-Hill.

- Marilyn S. & Michael, W.C. (2005). History of Art (4th Ed). London, P: New Jersey.

Michael. M (2011).Art & Design : Comprehensive Guide For Creative Art. makerere University. Kampala, retrieved on October 2019. https://www.aaltodoc.aalto.fi

Subscribe now for updates from Msingi Afrika Magazine!

Receive notifications about new issues, products and offers.

What's Your Reaction?

PIN IT

PIN ITMr. Wanyama Ogutu is a scholar in the Master of Arts (Fine Arts) program at Kenyatta University. He is also a practicing visual artist specializing in drawing, painting, and sculpture within, Nairobi, Kenya. He focusing in Painting with its’ philosophy, education and extension to Africa contemporary Art. Most of his artworks focus on interaction, environment, and education. Wanyama has a passion for fine art research; its philosophy, development, and relevance. He writes on profound academic topics, where he has presented and published in international journals and conferences around the world. He is a consultant in innovation and creative strategy on issues affecting our society. He is currently a part-time teacher at some TVET institutes within Nairobi.