The Gen Z Occupy Parliament Protest Art

Mr. Wanyama Ogutu is a scholar in the Master of…

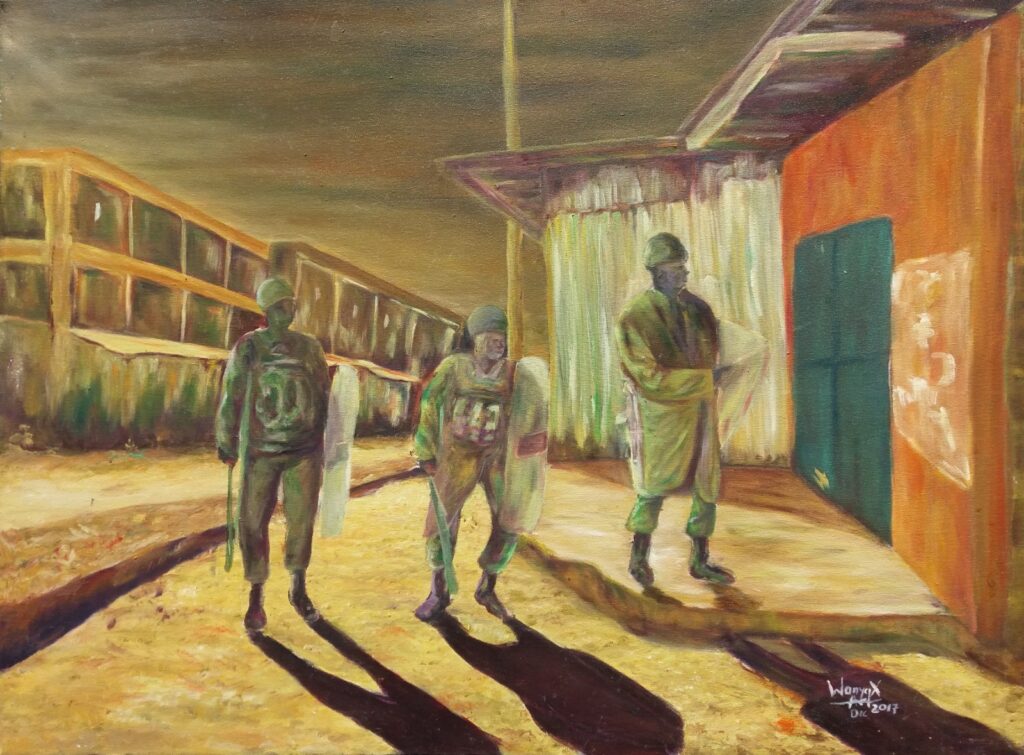

Title: Unit-Riot Police, Media: Oil on Canvas, Artist: Wanyama

Title: Shooting at Sharpeville, Media: Acrylic on Canvas,, Artist: Gogfrey Rubens

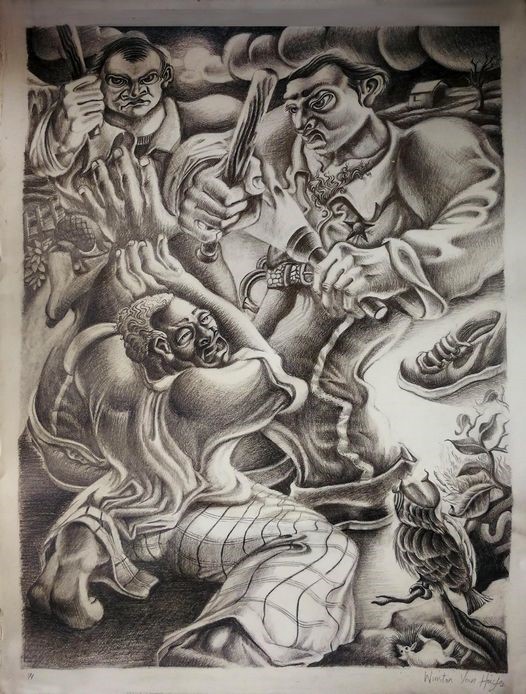

Title: The Oppressed, Media: Granite on drawing paper, Artist: Van Hughes 1994

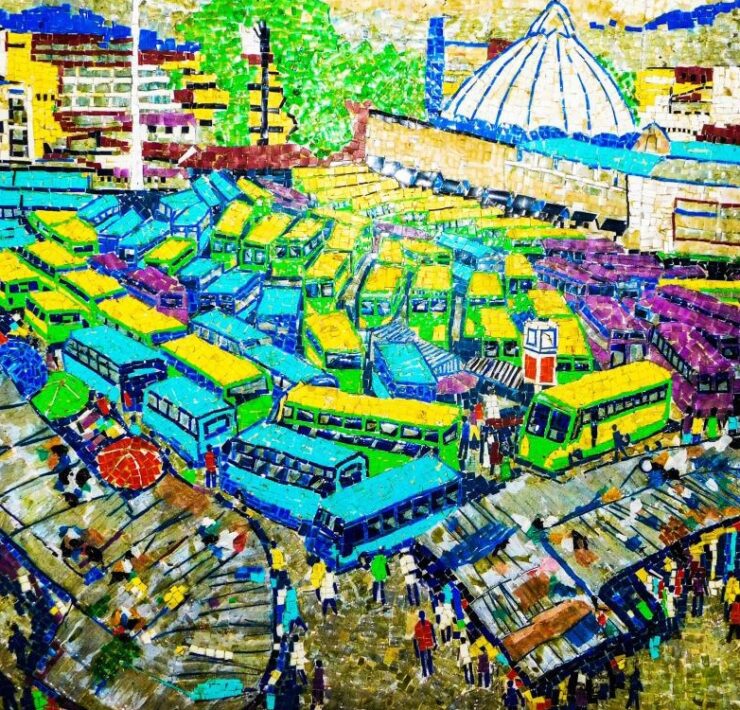

Freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed, according to Martin Luther King Jr. The oppressed voice must be heard. It was a day of high drama; the wail of sirens, flashing lights, and the spray of water cannons advanced toward the protesters. Gunshots, blasts of teargas canisters, and irritating pink water splashed all over the parliament building. Men and women of all colors—short and tall, thin and fat, white and black—were taking power in their hands. Some were running up and down; others fallen by gunshots, shaking their heads, legs, and torsos; while others were trampled on the ground, crying for a loaf of bread. The parliament was on fire. “Reject Finance Bill 2024!” the youths known as “Gen Z” shouted in unison. They held a Kenyan national flag, a bottle of water, and a smartphone. The contingent of police officers was running in confusion, shouting in their radio calls. “Afande! Pukei! Out of control!” Others were trembling with the Ak47s and bloody clobbers in their hands. “Kulutu! Piga Ua Yeye!” Pukei ordered. (“You recruit, shoot, and kill that one!”) A young police officer aimed an Ak47 gun at protestors; five were down, and another crowd of protestors surged toward the parliament like a relentless tsunami flood. Later that evening, I watched live recordings on various social media of members of parliament who escaped through an underground tunnel to the statehouse. I saw assorted footage of stranded parliament officials being rescued by military helicopters from the tops of skyscrapers. Some women members of parliament stuck a rack of clothes on their bellies and fled in ambulances, pretending to be critical patients for birth. That night, the president called the theatrical event “treasons and an act of criminals!”. A similar statement was declared in South Africa during the apartheid struggle.

There was an eye-catching placard of a pig-headed man stacked behind a skeleton cow. The hands were groping cow’s jujus while calves stood helplessly mooing in distress. The pig-headed man was bursting into hysterical laughter, his eyes fixed on the distressed calves. Another notable placard showed a rat perched at the top of a tree, surrounded by a cluster of cats mewing and meowing below. It had, written, in bold red letters, “Zakayo Shuka.” (Come down, Zacchaeus) “Anguka Nayo” (Fall with it). Suddenly, I saw a huge black police officer point his radio call antenna toward the crowd. I guess he was Afande Pukei. He wore a jungle army uniform written on his chest, “PUKEI ARAP PUNGE,” and a cap on his forehead with an emblem written “UTAISHI KWA WAPUNGE.” Two youthful plain-clothes policemen covering their faces like Al-Shabaab militia with long guns jumped out of a running van, heading towards the crowd leaders. The placards were in pieces, and men lay down flat, oozing blood and water from their necks. The people had been violently robbed of their right to reject punitive taxes. They could do nothing at all other than fall on the state instrument of enforcement. In this case, the living conditions for the people were already difficult. The Finance Bill 2024 was set to make life unbearable for Wanjiku ( he common man). The cost of living for Mama Mboga (vegetable sellers) was set to skyrocket. A loaf of bread and ugali (a staple Kenyan dish made from maize flour) would become unaffordable. The prices of milk, meat, and vegetables were set to rise beyond what workers could afford. The poor boda boda (motorcycle taxi rider) would find it even harder to provide food, clothing, housing, and medical care. Generation after generation, the mtu wa mkokoteni (cart puller) lives a life of desperation. A person whose parents suffer in poverty has two options: to tolerate the despair or change the status quo. They had been dragged to the edge of the river, and they had no choice but to swim with the crocodiles and snakes. The parliament burned.

The term “protest” came to prominence when Martin Luther opposed the oppressive rule of the church. His ideology divided the church into two opposing movements, known as Protestantism and New Catholicism. During this period of dictatorship, the church oppressed its citizens and denied them fundamental rights. The clergy and state officials were tyrannical. They conducted themselves worse, much like the Sadducees and Pharisees depicted in the Gospels of Saint Matthew and Luke. In response, Martin Luther nailed his famous Ninety-Five Thesis to the door of All Saints’ Church in Wittenberg, Germany. His master’s thesis challenged the oppressive state-church leadership and called for the division of the church. Drawing on Jesus Christ’s words, “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” Martin Luther further argued that every Christian should be a Christ to their neighbor. In 1937, Pablo Picasso created a modern protest artwork called “Guernica.” It was a powerful anti-war statement that memorialized the struggles of Guernica, a town in northern Spain, where many died during the Civil War. The painting depicts twisted human figures and animals in states of agony. Jacob Lawrence, an American artist, was deeply passionate about addressing racial inequality. His paintings portrayed the causes, effects, and turmoil of the Great Migration of African Americans. His work opposed the oppressive Jim Crow laws that threatened the lives of black people. His art sought to liberate African Americans from oppression and police brutality.

Protest movements were dominant during the age of modern technology, playing a crucial role in agitating against oppressive governance across the continent. The period gave rise to modern heroes of the 1960s, such as Martin Luther King Jr. in the United States, Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana, and Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt. It was a period that escalated the independence of over seventeen African nations from colonial power. International protests marked a significant epoch of protest art following the Sharpeville Massacre in South Africa. It was a period of amplifying the powerful sentiments of Pan-Africanism. For instance, the wide protests in South Africa sharpened the international political conversation in the United Nations Assembly in New York. It was an era of protests against black segregation in Birmingham and Alabama, among other 1960 protests. The world demanded the release of colonial prisoners and freedom fighters in African nations, such as the late Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya, among others. The protest agitation was heard everywhere in pockets of the world. As the saying goes, “Unless the hunter tells the story, the hunt will be glorified.” Protests erupted in cities, with people carrying protest art and demanding justice, often met with brutal repression. Police dogs were unleashed on protesters, and many were gunned down before the sun. The events of the 1960s bear a striking resemblance to the recent “Occupy Parliament”. Many protesters were left bleeding, abducted, and tortured, and some have disappeared without a trace to this day.

The Saba Saba 1990 was another historical year when Africa demanded multi-party democracy. It was also the year Nelson Mandela was released from prison, a symbol of the broader struggle for freedom and the new frontier of multi-party democracy. General Mathieu Kérékou of Benin and Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia lost power to Africa’s multi-party democracy. It was a period when prominent figures such as the Anglican bishop of Kenya, the late Alexander Muge, died in the struggle for multi-party democracy, and many, such as Gitobu Imanyara, were arrested by the late Moi’s regime’s instruments. Since then, multi-party democracy has evolved into a creative means of protest under Article 37 of the Constitution of 2010. It states that every person has the right to peacefully protest. The daily newspaper cartoons and caricatures in street art have been instrumental in exploring the power of this constitution, discussing and displaying protest art on issues such as corruption, poor governance, and police brutality. Beyond multi-party democracy protests in African nations, notable protests have emerged globally, including the Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011 in Washington, D.C., which was a stand against economic inequality. The 2003 Anti-Iraq War Protests saw global agitation against the U.S. invasion of Iraq. The Women’s March in 2017 advocated for women’s rights, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual (LGBTQIA) rights, and racial equality. The Teacher strikes in 2018 and 2019 across various countries demanded better pay and good working conditions. The murder of George Floyd in 2020 sparked an extraordinary wave of protest art, expressing solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement seeking justice and equity in the United States. Recently, the Occupy Parliament, a movement against punitive taxes, saw the president reject the Finance Bill 2024. It showcased the power and influence of protest art against oppressive governments.

The Kenyan Constitution of 2010 encourages imagination and creative art in peaceful protests. Artists are agitating through their artistic creations, using their talents and expressive gifts to support protests in the streets and at key locations. Both local and international media are spotlighting protest art as a powerful tool for liberation, advocating for LGBTQIA rights and women’s rights, challenging oppressive laws, addressing inequality, combating police brutality, and calling for fair governance. Protest art plays a role in pushing for the removal of ineffective governments, championing civil disobedience, and expressing collective grievances. These artworks communicate powerful messages through striking imagery, distorted illustrations, and bold, straightforward typography. Mimicry drawings and twisted artwork are often used to magnify the subjects of contention, making the messages even more impactful. As people march in the street protesting, the art becomes bigger and bolder, delivering clear and compelling messages to the globe. Recently, the power of protest art was instrumental in the ousting of Bangladesh’s Prime Minister, Sheikh Hasina. This example highlights the significant influence protest art can have in driving political change and demanding good governance.

The modern internet is revolutionizing ideas on social media at unprecedented levels. The myriad of information about protests can now be instantly disseminated, connecting people across the continent. This connectivity creates a global community where protesters share identities, values, and beliefs. Protest arts are known for their vast, colorful, bold, large-scale, and direct communication. They are becoming increasingly prominent and influential in protests. Now social media is amplifying agitation where public figures are scrutinized, and followers often step up as leaders. The primary issues addressed include sustainable good governance and the creation of environments free from oppression. Social media is effectively communicating vital concerns within society. Recently, protest art has had a significant global impact, challenging governments and demanding the removal of unfavorable leadership. The Occupy Parliament—Finance Bill 2024 protest, compelled the president to respond by rejecting punitive taxes. The protest art not only reshaped the government but also altered global perspectives on the demand for good governance. The influence of protest art has sparked other movements in countries like Bangladesh, Nigeria, and Uganda. Political scientists acknowledged the growing power of protest art to push for governance reform. They argued that the voice is becoming clearer, louder, and crucial in promoting accountability. They even encouraged every generation to fight for a certain course in life through creative means such as protest art. The creative fighter should never be faint-hearted or short of innovative ideas.

Reference

- Halliday, C. (2016). Arena For Contemporary African, African-American And Caribbean Art Street Art: Taking Art To The People. Https://Africanah.Org/Street-Art-Taking-Art-To-The-People-2

- Macfarlane, R. (2017). From The Dadaists To Guerrilla Girls, Here Are The Most Politically Impactful Artists Of The Last Century. Https://Www.Format.Com/Magazine/Brief-History-Protest-Art

- Mandela, N. (1994). Long walk to freedom: the autobiography of Nelson Mandela. Boston, Little, Brown.

- Smith, J. (2006). Multiparty democracy and political change: Constraints to democratization in Africa. Africa World Press, Inc.

- Srikrishna .R. (2020). The Power Of Protest Art :Dame. Https://Www.Damemagazine.Com/2020/08/17/The-Power-Of-Protest-Art/

- White, A. (2020). The Art Of Protest: A History Of Resistance. Https://Www.Shutterstock.Com/Blog/Protest-Art-History?Gad_Source=1&Gclid=Cjwkcajwyo60bhbieiwahmvljubjelgbwhbaf_W0va3-Mkhc2grqhhwnnkep-5u4pow40jbfjojgkboce04qavd_Bwe&Gclsrc=Aw.Ds&Kw

What's Your Reaction?

Mr. Wanyama Ogutu is a scholar in the Master of Arts (Fine Arts) program at Kenyatta University. He is also a practicing visual artist specializing in drawing, painting, and sculpture within, Nairobi, Kenya. He focusing in Painting with its’ philosophy, education and extension to Africa contemporary Art. Most of his artworks focus on interaction, environment, and education. Wanyama has a passion for fine art research; its philosophy, development, and relevance. He writes on profound academic topics, where he has presented and published in international journals and conferences around the world. He is a consultant in innovation and creative strategy on issues affecting our society. He is currently a part-time teacher at some TVET institutes within Nairobi.