LAMU: Love and Affection of Swahili Wedding

Mr. Wanyama Ogutu is a scholar in the Master of…

I was gifted with an intricate floral kofia (Islamic cap) and adopted a Swahili name upon visiting the nearby mosque. I wore the kofia with a long-sleeve shirt and kanzu whenever I went to the mosque. Sometimes, I put on the kofia to protect my forehead from the scorching sun. I embraced my Swahili persona, embellishing my body complexity, tall, slim, and light skin. Occasionally, I liked to clad the kofia with a favorite football jersey, especially when Arsenal won against Manchester United in the Arsenal Premier League. I spoke slowly like a native Lamu speaker, but my speech deficiency filled many eyes with tears of laughter. I also chose my words carefully, often finishing with an English sentence to bridge the speech deficiency. I had the wonderful opportunity to visit my friends at Jumba la Swahili, where I enjoyed a delicious meal of samaki ya kupaka (succulent fish cooked in a rich coconut sauce) and biryani (a fragrant rice dish full of spices). Most of the time, young boys riding donkeys offered me a free ride through the bustling narrow path of Lamu town. I exchanged “As-Salaam Alaikum Warahmatullahi Wabarakatuh” greetings with men in kanzu and women in buibui. A phrase that solidifies a sense of Islamic religious affiliation. At cock crow, I enjoyed strolling along the beach tasting kahawa tungu (a robust coffee). During lunchtime, I made my way to the delicious aromas of Mama Rukia’s Swahili dishes. In the evening, I found solace in the nearby mosque for prayers. Then, walked through the dark vichochoro, eventually rounding up my night at Mkunguni (Lamu Square) where we gathered to soak in local and international politics. Mkunguini was an animated assembly with a vitriol push of those who understood politics. The arguments were a reminder of the spirit of Bunge la Wanainchi in Jacaranda, Nairobi.

I come across a popular man at Mkunguni known as Sir Mwenzangu. He seems a humble and polite man, but people know him as a malicious and scheming person. He spoke with the confidence of someone well-versed in both local and global politics. It was rumored that he was a deportee for overstaying his visa in a foreign country. Sir Mwenzangu was a man of vitriolic argument, and he was never defeated in any cross-exchanges. He emerged victorious in any altercation. He was too shrewd a man, serving as a senior officer in the county government. Sir Mwenzangu valued my contributions and occasionally mistook me for famous figures like Nuru Okanga and Babu Owino. The man was fond of highlighting my eloquence in public with enthusiastic applause. One day, a stone struck my ear, and within a second, another stone hit my kofia. Everyone took to their heels in different directions. I covered my head under a scattered bench. I saw a shadow of a boy in a kofia disappearing like a rat running towards its hideout. I vividly recall someone constantly interjecting my speech with abusive words like mkafiri! kaongo! kasongo! (a liar outsider). I tried to locate the voice from the crowd, but it was camouflaged by a crowd of Islamic attire. I had energized the crowd in support of the impeachment of a senior officer. In the following meeting, I was cautious of my discussion. I gave more weight to issues that resonated with the crowd, such as opposing LGBTQ rights, condemning divorces, and single parenting. The crowds were at peace with my subject of discussion. I learned that family was a cultural thread of Swahili culture.

“Allah Hu Akbar” alarmed the people of the Lamu island for the evening prayer. The man cleared his throat and said, “matangazo za nikah”(weddingannouncement). He announced an upcoming wedding at the mosque and grand wedding reception at Mkunguni. I phoned Mr. Satan to confirm that those teenagers flirting at kichochoro were indeed planning to get married. They had already expressed their intentions to kutangaza nia (propose), and their parents had approved the union. I was excited to gatecrash the nikah event at the mosque and the walimah (wedding reception) at Mkunguni. That night, l tried to sleep but my anxiety would not let me close my eyes. I reclined on my bed, sleepless, curious to attend the nikah ceremony. I woke up at dawn, ironed crisp white kanzu, and cleaned my kofia. It had some spots of stone marks. The morning atmosphere was filled with the rhythms of drumbeats, lively laughter, and the stampede of people. I quickly put on the kanzu and I joined the colorful procession of drumbeats. A vibrant throng of children and women danced joyfully to the pulsating drumbeats. They traversed the vichochoros to the mosque. I followed them closely, minding my identity as mkafiri (an outsider). I elusively took a back position to catch a glimpse of the nikah event at the mosque.

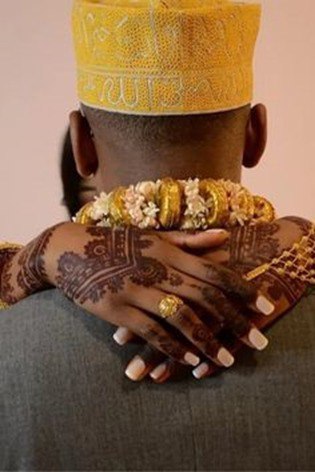

The bride was radiant, with a beautiful purple garment. Her arms and legs were embellished with ‘piko’ and ‘henna’ (body decoration). Her nose, ears, and neck were sparkling with jewelry. Her face was glowing like polished sand, and her eyes were glittering like diamonds. She was surrounded by her family. The boy was standing on the opposite side, clad in the royal regalia of the Sultan of Oman attire. When l stretched my neck over the crowd, Aha! It was the boy who stoned me at Mkunguni. I was shocked that the boy was accompanied by Sir Mwenzangu. He was his biological father. I remembered a shadow of a boy in a kofia disappearing like a rat. I wanted to spring out and accuse the boy of attempting murder. On the other hand, I feared Sir Mwenzangu would call me mkafiri. I knew my accusation would not stop the nikah ceremony. They had already completed kisomo and kupeana stages ofpre-wedding ceremony. I watched the Imam standing between them, adorned in Islamic attire and kofia. He read some Arabic words from the Quran, which were repeated many times by the boy and his bride. Finally, they were served with halwa, kahawa tungu, and kipande cha mbuzi (morsels of goat meat). At the end of the nikah ceremony, the Imam did not declare the couple as newlyweds. The bride was expected to graduate to kitanda cha ushutu (a bed for a pregnant mother) and bembeya (a bed for a nursing newborn baby). Nursing a baby was a sign of family commitment in Swahili culture.

After a successful nikah ceremony, the siwa (it is a big horn blown during special occasions like weddings) thundered through the air and was punctuated by the melodious call from the nearby mosque’s loudspeaker. The rhythms of drumbeats charged an atmosphere with celebratory jubilation. Women burst into ululations, shouting “Walimah tunayo sasa!” (we have the wedding). The colorful procession swiftly made its way toward the Mkunguni grounds. The couples joined the jubilant procession drumbeats. Although reception was a short distance from the mosque, the lively procession transformed the journey into a delightful adventure of approximately ten kilometers. Upon reaching the Mkunguni grounds, the procession was greeted by a breathtaking jubilation of attendance. The reception was beautifully designed like a king’s palace. They were arrays of vibrant colors of green, purple, and the fragrance smell of Udi. The guests and families gathered under a canopy of colorful fabric tents. The boy and his stunning bride lit up the reception with joyful smiles. Men sat on the baraza (a raised cement floor for relaxing), and some slid against the adjacent walls. Women sat on the floor in glittering buibuis andsparkling jewelry on their necks. Young ladies without hijabs were swaying their backs and hairstyles to the rhythms of ngoma za vugu (wedding dance). I watched from a distance and remembered the hijab lady in Lamu Tamu Express.

Suddenly, a man leaped from the crowd and violently grabbed a chubby woman at her back. They both tumbled to the ground, and everyone burst into laughter on top of their voices. A sympathetic woman screamed and ran to rescue the chubby woman on the ground. Two men violently pulled the man from on top of the woman and punched him. By this time, the chubby woman was struggling to regain her composure. Her face flushed with anger and pointed an index finger at his eyes, “Shika adabu!” (get some manners). She agitated, “We nitakufinya!” (I will pinch you). Everyone laughed again. The chubby woman stood up and continued to sway her back to the rhythm of ngoma za vugu. At one point, the chubby woman would weave tales of romantic mashairi (poems) to the couples. Her words were rich in seductive Swahili phrases that underscored the essence of love in marriage. Every man and woman’s heart was filled with awe of love and affection. The atmosphere was filled with aromas smell of Swahili dishes such as chakula cha mkono (a traditional Swahili feast for weddings), mikate ya sinia (fragrant biryani), vitumbua (crispy), sambusa (samosas), pilau, and kuku wa kupaka (coconut chicken). I swiftly made my way to indulge in biryani, and vitumbua that were passed to the men. Laughter echoed through the air mixed with jovial tales and hilarious gossip about the chubby woman. Everyone laughed loudly. The event ended with melodious sounds of taarab music composed by renowned poet; Ali Bin Ali. I watched the couples dancing while cuddling each other to a swift rhythm of taarab melodies. They were shimmering in romance and their face were radiating a bright future.

The Swahili weddings are among the most celebrated and esteemed cultures in East Africa. The culture is deeply rooted in the Islam religion and Swahili traditions. The Swahili marriage shares similarities with Arab, Persian, and Hindu customs. The marriage factor issues like blood relations, religion, tribal affiliations, wealth affluent, and less privileged. Social status is taken very seriously by both families during kuposa (proposal), kisomo (pre-wedding prayers), and kupeana (exchange of gifts or dowry). The engagement starts with lively celebrations that feature vibrant Swahili drumbeats, dances, and music. A wide variety of Swahili dishes and cuisine are served during kisomo, kupeana, and walimah (the wedding feast). Upon agreement of marriage, the groom presents the dowry to the bride’s family, which may include money or furniture. The wedding festivities start with the nikah ceremony (marriage contract at the mosque) and end with walimah event (grand ceremony at an open field). The newborn baby signifies the formal union of the Swahili marriage.

DECLAIMER:

The writer is not an expert or a scholar in culture especially Swahili culture. It is possible to miss the facts about Swahili wedding events or misinterpret the truth about Swahili marriage.

What's Your Reaction?

Mr. Wanyama Ogutu is a scholar in the Master of Arts (Fine Arts) program at Kenyatta University. He is also a practicing visual artist specializing in drawing, painting, and sculpture within, Nairobi, Kenya. He focusing in Painting with its’ philosophy, education and extension to Africa contemporary Art. Most of his artworks focus on interaction, environment, and education. Wanyama has a passion for fine art research; its philosophy, development, and relevance. He writes on profound academic topics, where he has presented and published in international journals and conferences around the world. He is a consultant in innovation and creative strategy on issues affecting our society. He is currently a part-time teacher at some TVET institutes within Nairobi.