Mr. Wanyama Ogutu is a scholar in the Master of…

Whatever we see following a man, whatever fate comes to take revenge on him, can only be what a man in some way did in previous years. It is what our forefathers believed during a devastating period. I was among the village heroes in my rural home during the lockdown of the year 2020. Indulging in ‘Busaa, Chang’aa, and Eng’uli’ (illicit alcohol), luring primary school girls with goodies, and touching widows’ ‘jujus’ were our hobbies. I got tired of such sickening behavior when I was caught red-handed in the wee hours of the night. I narrowly escaped a poisonous arrow by a whisker, targeting my left eye; I would be a one-eyed man. This time I sat quietly in my mother’s grass-thatched kitchen, watching a hen in the corner lay on three eggs. It hatched one chick, leaving the other two to struggle in the eggshells. I observed other chicks so sympathetically as they were struggling to come out of the eggshell. Oh, I decided to help the chicks come out of the eggshell. I picked up a needle and a pair of scissors, then successfully removed the chicks with no harm, like neurosurgeon Ben Carson operating the brain. The day and week passed; the chicks became weaker and weaker, and, eventually, they died. It happens when a man finds an easy way out of life amid devastation.

The casket was not there during the funeral of my friend’s third ‘wife. She had been buried the day after she died of the COVID-19 pandemic. My friend would occasionally stand up to the mourners and boast that he was better off. He was burying his third wife, while I was languishing in poverty in the city’s slums. He used the analogy of a cock without a spur foot to describe my personality in public. Everyone burst into laughter, at the top of their voices, while looking at me. A week later, I arrived in Kayole, full of humiliation and bitterness. I remember the loud laugh from my bald uncle, Chebukati, who had not wanted me to finish class eight. Lately, he felt so bitter when I graduated with a diploma in house help. As I walked toward my house, the ‘boda boda’ almost knocked me down when he speedily crossed the road without looking or signaling. The young boda boda rider in a T-shirt written “Asolar Wa Ruto” looked back and raised his middle finger in disgust. At that moment, everyone was running up and down in fear of city ‘askaris’ that would arrest them. The askaris were enforcing the order from above on the COVID-19 curfew. I had carried a red-black cock on my left-hand side that kept on making cock-a-doodle-do noises, a bag of maize on my shoulder, and dried, smelly Mbuta fish in my right hand. Still, the humiliation sank so deeply that I dropped on my mattress like a jackfruit falling from a tree. “Why would that lunatic widower insult me in public?” I slept, thoughts jumping through my head. I dreamt wrestling the lunatic to death like two cocks fighting.

The devastating COVID-19 radio slogans “Kaa Nyumbani Angamiza Korona,” “Korona iko kwa Wazee na kwa Vijana,” ”Hata Watoto Hawashazwi,” and “Jikinge na Korona” (“Stay at home.”; “COVID-19 kills both the young and the old; children are not safe too.”) echoed through the central water point in our rental block far away. I gossiped with some female neighbors while washing clothes at the central water point. It was a center of information for many neighborhoods’ secret affairs and full of hysterical laughter in different tones and voices. No neighborhood was left behind in the gossip. Occasionally, a fight would break out between antagonistic women for revealing their neighbors’ gossip. We knew that our landlady was the widow of a rich man who had two sons, and her sons were serving long-term sentences for bank robbery with violence. The landlady inherited millions of dollars after winning a court case against her brother-in-law. Last month, her rental houses were demolished by city askaris for building on stolen land. The landlady had prepared a grave for her own, only to be buried in it.

During the lockdown in 2020, we were arrested and jailed in Corona prisons in our houses and homes, a style adopted by President Museveni of Uganda against his political opponents. I had moved to another Mabati new rental house next to the former landlady’s rental plot. I saw an opportunity to hold an art session at the water point. This time, it was dry without a crusade of gossiping women. The caretaker knew the consequences and ensured the water taps were dry during the daytime. For me, it was an advantage to transform the water point into an art space. Within five days, I had attracted a large group of children, for whom I demanded 10 shillings each. I remember the children running up and down, playing with clay, some screaming and shouting with excitement. Their faces were full of paint, and their clothes were stained with colors. Some children drew my head, comparing it to a hare’s ears and a monkey’s face. Little did I realize that my neighbors were infuriated with me. I later learned that some children were stealing money from their parents.

Before the rays of sunshine blocked Nairobi’s skyscrapers from the east, I heard spotless rubber scandals sounding toward my house. A baggy pair of trousers, an untucked short-sleeve shirt, and a red-colored faded cap on his forehead stood written “Ni Mungu Tu” (It is only God). He flipped open the black-faded door curtain. “This is Nailopi!” (This is Nairobi), he uttered in English colored by his mother tongue as he sniffed air while battling the flu. He then vanished out of my sight, humming music: “Maya ni mabatarao makwa, “Ngai hingiria, ndunyihanyihiirwo.”” (These are my needs; oh God, please provide; you are not lacking.) “A week did not end; I did not see any children coming around me. Some children remained in their houses, just looking round the edge of the doors. There was a deep silence in the plot building, and no child stepped out or raised voices of joy. Any time I placed my paint and easel at the water point, no child came out. Some children playing along the stairs would frown and run away, shouting “Wooi Mwendaa ndo huyu” “Wooi Mwendaa ndo huyu (here is a madman).

PIN IT

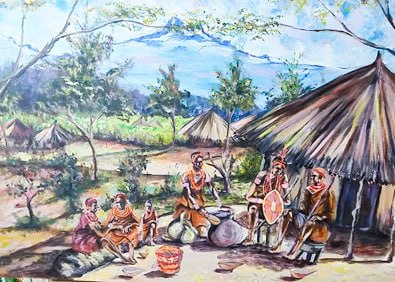

PIN ITTitle: Obey the curfew, Media: Acrylic on Canvas, Artist: Wanyama

An intrusion of cockroaches and bedbugs scattered to bed hideouts occurred when I angrily crushed my small radio against a dusty floor. Indeed, I was tired of the devastating COVID-19 slogan vibration that made life hopeless and meaningless. The following night, I was in the city, wandering, and with no help. The sirens and lights flashed from askari’s vans with alarming noises. People were running up and down in fear of being whipped or clobbered by askaris. “Obey the curfew order! Ghasia hii!” The short askari raised a voice with irritation. The whips landed on my buttocks. I fell in pretense, shaking my legs and torso like a lizard. “Afade!.., Hii ako Korona! … Ida ambules!””This one has corona, call the ambulance” One askari shouted as he stood aside, trembling with the whips in his hand. “Ambulance!”. The other askari shouted at the radio call. I was in the back of the ambulance van on my way to the hospital. As the vehicle was speeding to the hospital, I planned how to get out. After a long drive, the van stopped at a police roadblock entering the city center at night. Police with guns in their hands and masks on their faces were manning the highway to the city center. “Afande!. Hii Gonja wa Korona!” The sharp voice emanated in front of the van. The askari flashed their eyes left and right inside the ambulance van. Little did they know, I flung the door of the ambulance van and flew on foot like a rat running towards a hideout. The askaris also flew out in a different direction as the ambulance van sped off in another direction.

I stopped at the waiting truck at the petrol station, heading in the direction of my rural home. I pleaded with the truck driver for a ride, and eventually, I was riding in the back of the truck. I arrived in my village early in the morning and immediately reconnected with my classmate’s friend, now a widower, and a lunatic village drunkard. It had been a long time since he lost his job as a city askari for not leaving a bottle of tips. An African elder once said that if a senior bachelor crosses a great river to marry a wife from far away, he must be ready for the risk of a night journey. My friend had divorced his first wife; his second wife drowned in the river, and now we were attending the third wife’s burial, who died of COVID-19 infection. His firstborn had been diagnosed with mental anxiety, and he was taken care of by his mother-in-law. Many gossiped that the atrocities were equated to witchcraft, and curses from a late grandfather. Others attributed an evil spirit to an uncircumcised divorced wife. We filled the night air of the entire village with the noise of vernacular songs on COVID-19. Many children never slept peacefully. During the day, we idled at a shopping center bar, making noises about village politics. In the evening, we siphoned ‘Busaa, Chang’aa, and Eng’uli’, then proceeded to intrude on single mothers and widows at their houses sexually. Oh, Sorry! This is African story fiction, an observation of the resilience and challenge of the COVID-19 period.

REFERENCE

DreamKona .(2021).The Art of Resillience: Kenya in Art in 2020. Trust for Indigenous Culture and Heath (TICAH)

Subscribe now for updates from Msingi Afrika Magazine!

Receive notifications about new issues, products and offers.

What's Your Reaction?

PIN IT

PIN ITMr. Wanyama Ogutu is a scholar in the Master of Arts (Fine Arts) program at Kenyatta University. He is also a practicing visual artist specializing in drawing, painting, and sculpture within, Nairobi, Kenya. He focusing in Painting with its’ philosophy, education and extension to Africa contemporary Art. Most of his artworks focus on interaction, environment, and education. Wanyama has a passion for fine art research; its philosophy, development, and relevance. He writes on profound academic topics, where he has presented and published in international journals and conferences around the world. He is a consultant in innovation and creative strategy on issues affecting our society. He is currently a part-time teacher at some TVET institutes within Nairobi.